Linux Shell Tips

I personally like using Linux systems. Although Windows has a better graphical interface, its support for scripts is poor. At first, I was not used to command-line operations, but after getting used to it, I found that moving the mouse and clicking is actually what wastes the most time.

This article is not about specific Linux commands. Instead, I will explain some details and tips that are easy to confuse and can help you work more efficiently, using real situations as examples.

The difference between standard input and command parameters.

Running commands in the background, but they all stop after closing the terminal.

The difference between single and double quotes in representing strings.

Sometimes, a command with

sudowill say "command not found".How to avoid typing repeated filenames, paths, or commands, and some other little tricks.

1. The Difference Between Standard Input and Parameters

This is a common problem. Many people don't know when to use the pipe symbol | or file redirection > and <, and when to use variables like $.

For example, I have a shell script called connect.sh for connecting to broadband, and it's in my home directory:

$ where connect.sh

/home/fdl/bin/connect.shIf I want to delete this script and type as little as possible, how should I do it? I tried this before:

$ where connect.sh | rmActually, this is wrong. The correct way is:

$ rm $(where connect.sh)The first command tries to send the result of where to rm as standard input. The second command sends the result as a command-line parameter.

Standard input means functions like scanf or readline in programming languages. Parameters are the string arrays passed to the main function as arguments.

In Linux File Descriptors, I said that pipe and redirection send data to a program's standard input, while $(cmd) gets the result of a command and passes it as a parameter.

Using the example above, the source code of the rm command does not accept standard input, only command-line parameters to delete the specified file. In comparison, the cat command accepts both standard input and parameters:

$ cat filename

...file text...

$ cat < filename

...file text...

$ echo 'hello world' | cat

hello worldIf a command will block the terminal and wait for your input, it means it accepts standard input. Otherwise, it does not. For example, if you just run cat without any arguments, the terminal will wait for your input and print what you typed.

2. Run Programs in the Background

Suppose you log in to a server and run a Django web program:

$ python manager.py runserver 0.0.0.0

Listening on 0.0.0.0:8080...Now you can test the Django service using the server's IP address, but the terminal is blocked and won't respond to your input unless you use Ctrl-C or Ctrl-/ to stop the Python process.

You can add & at the end of the command to run it in the background. This way, the terminal doesn't block and you can run other commands. However, if you log out from the server, you can't access the web page anymore.

If you want the web service to keep running after you log out from the server, use (cmd &) like this:

$ (python manager.py runserver 0.0.0.0 &)

Listening on 0.0.0.0:8080...

$ logoutThe underlying reason is:

Every terminal is a shell process. When you run something, the shell makes it a child process. Normally, the shell waits for the child process to finish before accepting new commands. If you add &, the shell does not wait and can continue to accept your commands. But if you close the shell terminal, all its child processes will stop.

If you use (cmd &) to run a command, it will become a child of the systemd daemon process, instead of the shell. So, when you close the terminal, this command is not affected.

There is another common way to keep a process running:

$ nohup some_cmd &The nohup command works for this too, but in my tests, using (cmd &) is more stable.

3. The Difference Between Single and Double Quotes

Different shells may behave slightly differently, but one thing is certain: if you use single quotes, characters like $, (, and ) are not interpreted, but double quotes will interpret them.

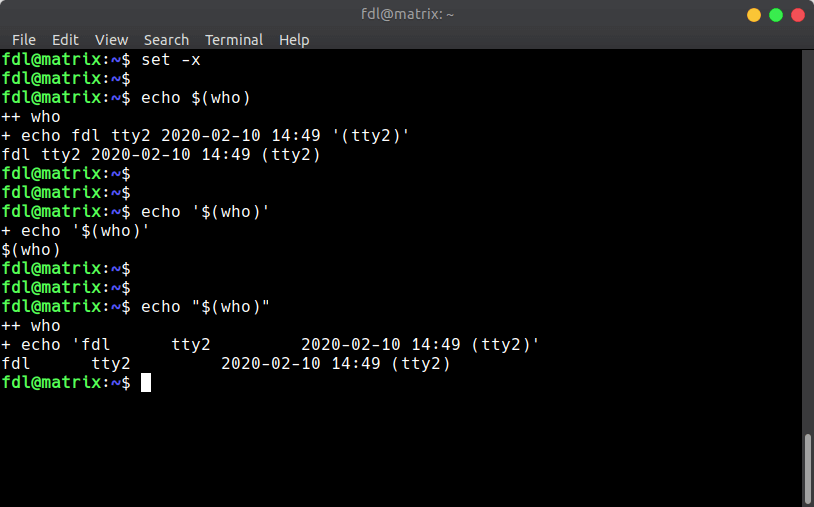

You can test shell behavior with the set -x command, which will show what the shell is really doing:

You can see that echo $(cmd) and echo "$(cmd)" have almost the same result, but there are some differences. Notice that with double quotes, the result adds single quotes automatically, but with no quotes, it does not.

In short, if the string from $ contains spaces, you should use double quotes, otherwise you will get errors.

4. sudo: command not found

Sometimes, a command works for a normal user, but adding sudo gives a "command not found" error:

$ connect.sh

network-manager: Permission denied

$ sudo connect.sh

sudo: command not foundThis happens because the connect.sh script is only in the user's environment:

$ where connect.sh

/home/fdl/bin/connect.shWhen you use sudo, the system uses the environment variables defined in /etc/sudoers. That does not include the script's path.

The solution is to run the script with its full path:

$ sudo /home/fdl/bin/connect.sh5. Typing similar filenames is annoying

You can use curly braces and commas to extend file names easily. Here are some examples:

$ echo {one,two,three}file

onefile twofile threefile

$ echo {one,two,three}{1,2,3}

one1 one2 one3 two1 two2 two3 three1 three2 three3Every item in the braces is combined with the string outside the braces. Do not add spaces inside the braces or around the commas, or it will not work.

This is very useful for commands like cp, mv, and rm:

$ cp /very/long/path/file{,.bak}

# This copies file to file.bak

$ rm file{1,3,5}.txt

# This removes file1.txt file3.txt file5.txt

$ mv *.{c,cpp} src/

# This moves all .c and .cpp files to the src folder6. Typing long paths is annoying

Use cd - to go back to the previous directory. For example:

$ pwd

/very/long/path

# Go to home directory

$ cd

$ pwd

/home/labuladong

# Go back to the previous directory

$ cd -

$ pwd

/very/long/pathThe special command !$ replaces the last argument of the previous command. Example:

# No execute permission

$ /usr/bin/script.sh

zsh: permission denied: /usr/bin/script.sh

$ chmod +x !$

chmod +x /usr/bin/script.shThe special command !* replaces all arguments of the previous command. Example:

# Created three script files

$ file script1.sh script2.sh script3.sh

# Give them all execute permission

$ chmod +x !*

chmod +x script1.sh script2.sh script3.shYou can add your common directories to the CDPATH environment variable. When you use cd, the command will search these directories if it can't find the folder in the current location.

For example, if you often go to /var/log, set it like this:

$ export CDPATH='~:/var/log'

# cd will now also search your home ~ and /var/log directories

$ pwd

/home/labuladong/musics

$ cd mysql

cd /var/log/mysql

$ pwd

/var/log/mysql

$ cd my_pictures

cd /home/labuladong/my_picturesThis is very handy. You do not need to type the full path every time, saving time.

Note: These commands work with bash. Other shell interpreters also support searching directories with cd, but you may need to set it up differently. Please search for how to do it in your shell.

7. Typing repeated commands is troublesome

Use the special command !! to quickly repeat the last command:

$ apt install net-tools

E: Could not open lock file - open (13: Permission denied)

$ sudo !!

sudo apt install net-tools

[sudo] password for fdl:What if a command is long and you can't remember the exact parameters?

In bash terminal, you can use Ctrl+R to search previous commands. This key combination searches backwards, finding the most recent command that matches.

For example, after pressing Ctrl+R, type sudo, and bash will show you the most recent command containing sudo. Press Enter to run it:

(reverse-i-search)`sudo': sudo apt install gitBut this method has some drawbacks: First, it only works in bash, not in zsh or other shells. Second, it only finds the most recent match. If you want an older command, it's not convenient.

In this case, the most common way is to use the history command with pipe | and grep to search historical commands:

# Filter all commands that include 'config'

$ history | grep 'config'

7352 ./configure

7434 git config --global --unset https.proxy

9609 ifconfig

9985 clip -o | sed -z 's/\n/,\n/g' | clip

10433 cd ~/.configAll the shell commands you use are recorded. The number in front is the command's index. After you find the command you want, you don't need to copy and paste. Just use ! plus the command number to run it again.

For example, to run the git config command shown above:

$ !7434

git config --global --unset https.proxy

# doneIf you think typing history | grep is still too much, you can add a function to your shell config file (like .bashrc or .zshrc):

his()

{

history | grep "$@"

}Now you only need to type his 'some_keyword' to search history.

I usually don't use bash as my terminal. I recommend a very useful shell: zsh, which is also what I use. Zsh supports many plugins and is easy to customize. You can look up detailed setup guides online.

Other Small Tips

1. The yes command automatically inputs y for confirmation

Sometimes when installing software, you get interactive prompts like:

$ sudo apt install XXX

...

XXX will use 996 MB disk space, continue? [y/n]We usually keep pressing y. If you're automating the installation, these questions can get in the way.

The yes command helps:

$ yes | your_cmdThis will automatically answer y for every prompt and won't stop to ask you.

If you have read Linux File Descriptors, you will understand why: The yes command simply prints a lot of y. By connecting its output to the input of your_cmd, any interactive prompt will get a y and newline, just like you typed it.

2. Special variable $? saves the return value of the previous command

In Linux shell, if the program ends normally, the return value is 0. If not, the return value is not 0. Reading the last command's return value may not seem useful in daily use. But if you're writing shell scripts, it's very useful.

For example, you want to add a footer to many markdown files automatically. Some already have it, some don't. To avoid adding it again, you must check if the footer already exists. Here, $? and grep help:

#!/bin/bash

filename=$1

# Check if the last lines contain the keyword

tail | grep 'page_footer' $filename

# grep returns 0 if found, non-0 if not

[ $? -ne 0 ] && { <add_page_footer_command> }3. Special variable $$ saves the PID (process ID) of the current process

This may not be useful every day, but it's helpful in shell scripts. For example, when you need to create temporary files in /tmp, you need unique names. You can use the $$ variable to get the process PID, which is always unique. You do not need to remember the file name.